On Friday evening I started writing about what I perceived to be last week’s hot topic, aka Microsoft’s release of its Copilot suite powered by GPT4, which I am convinced will be a true productivity game changer with significant consequences on the organization of work and the skills of professionals. That was Friday evening, before an ‘eventful’ weekend here in Switzerland, to say the least – and don’t worry, I should come back to GPT4 next week unless the world keeps collapsing in the coming days.

The news came down on Sunday evening: after several months spent on the brink, as a result of years of risky (and sometimes illegal) decisions, 167 year-old Credit Suisse (CS) has officially ‘joined forces’ its competitor UBS, in a ‘merger’ paid for exclusively in shares (current CS shareholders will receive 22.48 shares of the new group for each share they hold), valuing CS at around CHF3bn (USD3.2bn).

CS’ existing difficulties had been magnified in the past few days by the collapse of SVB, which we discussed last week. In a ‘hunt for safety’, customers rushed to withdraw their deposits (up to CHF10bn per day last week, according to the Financial Times), further weakening the already wounded animal. This sequence of events stresses once more the central role of trust (among other psychological factors) in the proper functioning of the banking system.

Coming back to the deal itself, the Swiss Federal Council justified the exceptional underpinning deal features (we will get to this shortly) by the need to protect the Swiss financial place. Banking regulators in Switzerland, Europe and US all welcomed a difficult but necessary move. If this deal satisfies the public authorities, it leaves a bitter taste to all other stakeholders and, once the immediate relief has passed, worries me more than reassures me.

First, the collapse will inevitably bring the issue of ‘moral hazard‘ back on the table, as it came in 2008. Indeed, bank executives and staff are rewarded when their decisions prove profitable (through hefty bonuses), but they are not made financially liable when things turn sour (the so-called ‘limited liability’). As a consequence, bankers always have an incentive to adopt a riskier stance than the one which would be dictated by putting the bank’s interests first.

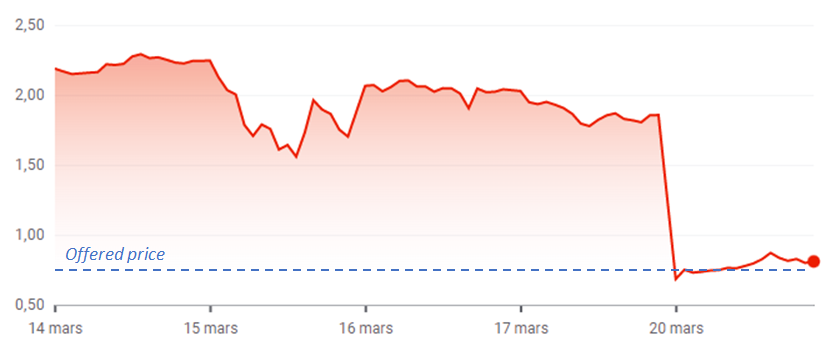

Furthermore, and more worryingly in this case, capitalist economies were able to develop precisely because the rights to capital were protected by a strong legal system, ultimately supported by the State. In this case, the exact opposite happened. The Swiss State will force existing CS shareholders to hand over their shares at a price (CHF0.76 per share) significantly lower than the one quoted by the stock market as of Friday evening (around CHF1.86). In a State governed by the rule of law, you cannot expropriate an owner without his consent at a price lower than ‘fair value’, which is the one determined by the market where it exists. And yet, when we regard shareholders as owners of a corporation, this is exactly what happened. Practically speaking, the Swiss State ‘stole’ CHF1.10 per share from CS shareholders over the weekend (a period during which stock markets are closed) and handed over the money to UBS in the form of a rebate over the purchase price. When we know that CS’s shareholders are partly sovereign wealth funds, there is no doubt that this episode will have meaningful diplomatic consequences…

Both lines converged after the offer was unveiled, resulting in a significant loss for incumbent shareholders.

Source: Google Finance

Debt holders have the right to feel doubly harmed. Not only were they totally wiped out, but they had to give way to equity holders, who for their part recovered part of their stake – whereas, in corporate law, debt instruments should be repaid before equity in case of liquidation. Such a violation of property rights sets a very damaging precedent, the consequences of which will affect public and investor confidence in the banking sector, not only in Switzerland but also worldwide.

The weigh on Switzerland’s public finances is also far from negligible. As part of the agreement, UBS indeed negotiated an array of default protection measures and liquidity lines guaranteed by the Swiss authorities, i.e. ultimately Switzerland’s taxpayers. Unsurprisingly, the reaction of the general public and the Swiss political world is since yesterday morning overwhelmingly negative. Even UBS’s shareholders do not seem entirely convinced by this merger, as expressed by the sharp drop in share price followed by an equivalent recovery, even though the bank announced its ambition to deliver CHF8bn in annual cost ‘synergies’, consequently putting an estimated 10’000 jobs at risk.

Finally, with more than USD5’000bn in invested assets, the merged entity will become the clear #1 bank in Switzerland and will further climb up the ladder of the banks earmarked as ‘too big to fail‘. In addition to the undeniable impact on competition (a consideration completely absent from this weekend’s debates), the liner will become even heavier and more difficult to save the day it takes on water – as was the case in 2008.

In my view, in one hand, saving CS through a merger was the only reasonable option that the Swiss authorities had at their disposal. On the other hand, they got cornered because of the serious failures of CS’s management team and its regulatory authorities. Without a complete overhaul of the rules of the game at a global level, it is not a matter of ‘if’, but a matter of ‘when’ another similar crisis will unfold. And, that time, a big enough lifeboat will be much harder to find.