Over the past several weeks, we have discussed various factors driving the present and future evolution of the job market, including demographic shifts, changes in the balance between blue-collar and white-collar jobs, workforce participation across genders and age groups, and the impact of new technologies such as AI. These long-term trends necessitate public policy responses. Addressing the problem upstream, we must also consider the transformation of higher education, which is crucial for enabling our societies to adapt to the changing landscape in the coming decades.

While not exhaustive, several trends are worth highlighting:

- An aging population: The increase in life expectancy, coupled with a decrease in birth rates, means that workers will need to work longer to support pension schemes and maintain economic growth. As noted in an earlier blog post, this creates a strong incentive for individuals, employers, and public authorities to invest in maintaining high employability levels across the population. This, in particular, involves addressing labour market friction or rigidity due to skill mismatches, where companies struggle to find suitable candidates for job openings while job seekers cannot find appropriate offers.

- A shifting macroeconomic environment: After decades of unrestrained globalization, the COVID-19 crisis and current geopolitical tensions have highlighted the importance of borders and geographical distances. National economies have started to support, sometimes with difficulty, the need to bring home certain “strategic” industries that were previously outsourced. This phenomenon has and will continue to affect the future demand for labour, increasing the value of previously undervalued blue-collar jobs within developed economies.

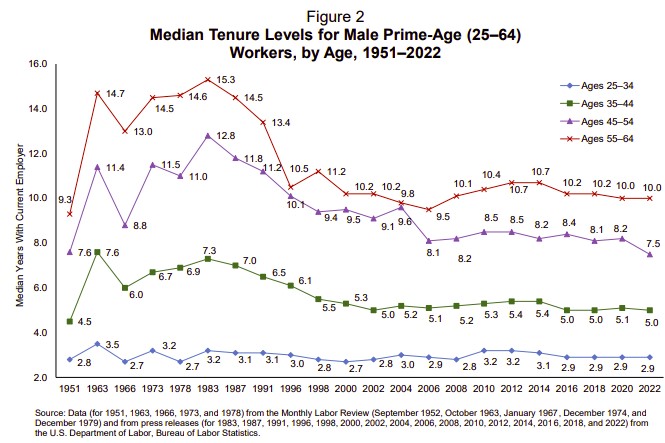

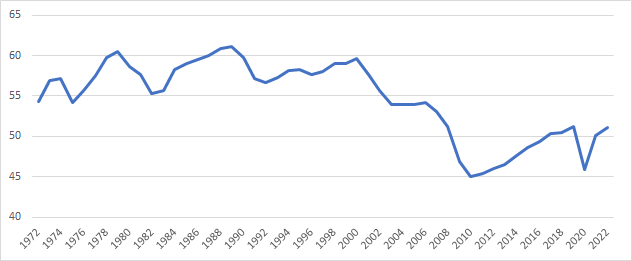

- Diversification of career trajectories: Lifetime employment is becoming increasingly uncommon, and over the past 40 years, job tenure has generally declined. This results in more diverse career paths and, combined with longer life expectancies and overall career durations, a higher likelihood of career changes. Recognizing the experience gained by Millennials in the current environment, characterized by start-ups and frequent job changes, will be a significant challenge.

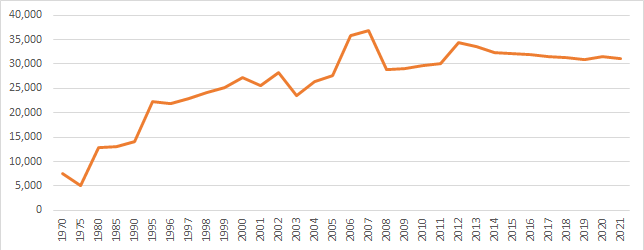

- An unsustainable economic model for higher education: The debt burden shouldered by graduating students has been steadily increasing, hindering future investment opportunities. In a highly debated action, President Biden proposed to forgive all student debt to boost spending. Regardless of whether this move turns out to be beneficial or merely inflationary, it demonstrates that the current higher education system is built on economically unstable foundations.

- A pervasive technology and innovation boom: In recent years, there have been remarkable advancements in communication (smartphones, 4G/5G, etc.) and content creation (crowdsourcing, social networks, Web 2.0, LLM, AI, etc.) technologies. This has significantly reduced the cost of retrieving and sorting information as well as creating and distributing content. The education sector has started to benefit from this phenomenon, albeit modestly, through investments in ‘EdTech’, which reached an estimated $21 billion in 2021.

How can higher education adapt to embrace the trends we have just outlined? A comprehensive answer to this question would require much more than a few lines, but we can offer some initial ideas:

- Imposing lifelong learning as a necessity: A few weeks ago, I cited research by Autor stating that the majority of today’s jobs did not exist 80 years ago. Given the pace of progress, it is almost certain that similar displacement will continue in the coming decades. This phenomenon will be felt both globally and nationally; for example, who would have thought 40 years ago that China’s older workers would express the need for more training to meet the new demands of the local economy?

- Valuing of a “T-shaped” interdisciplinary training model: In the future, easier access to specialized knowledge may shift the focus from advanced technical skills to the ability to understand and connect different business areas. Pure specialists may be replaced by “T-shaped” professionals who are experts in their fields but also capable of interacting effectively with their entire professional environment.

- Rethinking initial education: Developed economies tend to extend the duration of initial education. A bachelor’s degree or its equivalent is now seen as a “must,” and it often needs to be supplemented by a master’s degree or MBA to provide students with a comprehensive generalist background. Consequently, “young” graduates enter the job market later on average and use only a small portion of this knowledge throughout their careers. An alternative strategy would involve shortening the duration of initial education, making it more pragmatic, and supplementing it with a series of short, on-demand trainings to support career development. Technology could enable the delivery of a fully customized experience across all dimensions (pace, timing, delivery method, learning content).

- Prioritizing skills and competencies over experience: Due to non-linear career paths, it will become increasingly challenging to evaluate an employee’s value based on their years of experience alone. In this case, an employee’s added value can only be measured using a new reference system focused on skills.

- Fostering partnerships between educational institutions, companies, and governments: As mentioned in the first part of this article, employment and employability issues affect our entire society. It makes sense to involve businesses and public authorities more closely in designing training programs, even within private higher education institutions. As the primary observers of each employee’s actual performance and development, companies can also play a role in awarding “diplomas” or “skills certificates.” This will de facto require the establishment of a compatible system for recognizing “credits” between the world of education and the world of work.

- Embracing differentiation among education providers: The increasing accessibility of knowledge has lowered the cost of creating certain courses, enabling students to choose from a wider range of course types. At one end of the spectrum, MOOCs provide access to high-quality educational content at little or no cost. At the other end, premium institutions must offer not only exceptional educational content but also a first-class student experience, both on campus and after graduation (e.g., through alumni networks). The overall experience will become as important, if not more so, than the content itself.

As you can see, I am passionate about this subject and could discuss it at length. For now, I hope this initial overview has helped you perceive the complexity of the world in which we live, not as a threat but as a source of immense opportunities.