As I meandered through the opening chapters of my current read, Peter Zeihan’s “The End of the World is Just the Beginning” (a book now featured in My Library), my old reflexes resurfaced. The title, teetering on the precipice of doom and rebirth, made me (once again) reflect on the profound demographic changes we are about to face and the potentially drastic implications for our global economy. Unlike the book’s apocalyptic undertone, today’s post is not about a doom prophecy. Rather a call for us to understand, prepare, and adapt to the inevitable.

The wave of prosperity that developed economies have been witnessing over the last few decades has been relying (to a significant extent) on these economies’ abilities to constantly increase the aggregate value created by products and services while leveraging other economies’ lower salaries base to keep costs under control. Thanks to this ‘offshoring wave’, China, East Asia and, to a lesser extent, India and Latin America have become global manufacturing powerhouses.

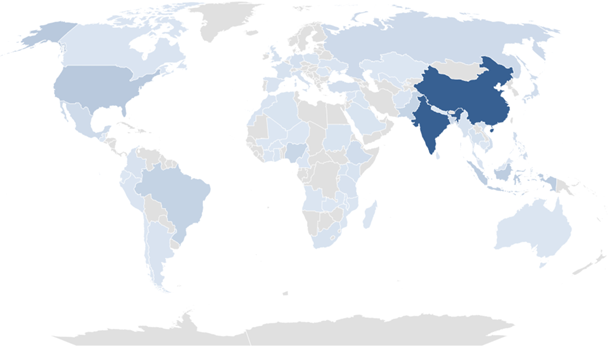

As our world became more uncertain and volatile, corporations have been looking for more flexible and responsive supply chains. This ‘hedging’ need has given rise to ‘nearshoring‘, with firms leveraging closer geographical locations to their primary markets under the belief that increased labour and raw material costs would be more than offset by an increased proximity with the customer and shorter production lag times, explaining why areas such as Turkey, North Africa, Spain, and Portugal have become attractive due to their relative proximity to major European consumer markets. Both offshoring and nearshoring were built on two premises, however: (i) those developing countries would keep offering a steady supply of working-age people (clearly still the case today as per the chart below) and (ii) transportation costs would remain relatively limited relative to the cost of the end-product.

We stand at a crossroads where those two assumptions are about to be challenged:

- The current geopolitical environment seems to lead us towards a new ‘Cold War’ opposing (to make it simple) the USA and Europe on one side and Russia and China on the other, with South-East Asia a contentious area among others. Undoubtedly, trade between those two blocks will become harder and more costly in the future. And yet, the Eastern block has been a significant provider of goods and services for the Western block. Our world is about to get more expensive.

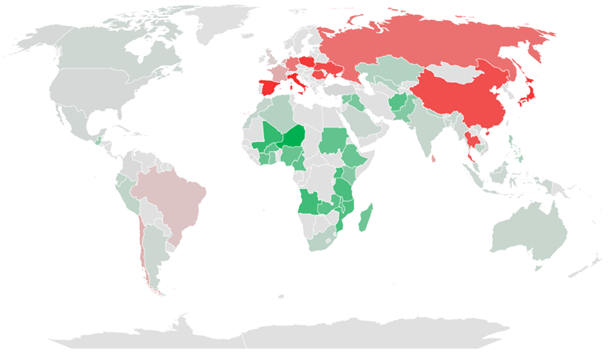

- The era of the abundant working population is coming to an end. Big time. The World Bank estimates that, by 2050, China’s 15-64 population will have shrunk by almost 220m people, South Korea’s by 13m, Thailand’s by 10m, Poland’s by 7m etc. A dwindling labour force implies a natural upward pressure on wages since the demand for goods and services will continue to be sustained by an ever-growing retired population.

Governments will obviously be at the forefront of efforts to find solutions to this now irreversible problem. Corporations will also need to adapt, though, starting with a review of their footprint. As the map above shows, significant population drops in traditional offshoring or nearshoring countries will likely put those models under pressure.

Going forward, they will have two major strategies available, not necessarily mutually exclusive: first, relocating to countries with growing workforce populations. North America could be tempted to bring jobs back ‘in-house’ given the positive demographic trend forecasted. Europe-based corporations will not have that luxury and will have to keep looking abroad for labour pools, primarily in India and/or Africa, with Nigeria expected to be the most demographically dynamic country. This latter solution, however, would require a stable environment conducive to business, marked by robust infrastructures, a secure political and legal framework, financial stability, and upheld property rights.

The second option, perhaps more universally applicable, involves investing heavily in process efficiency improvement. The deployment of automation and artificial intelligence could significantly reduce the reliance on human labour. A transformative approach that, while disruptive, might just be the key to ensuring sustainable operations in an era of shrinking labour pools.

At the end of the day, the future of our economy hinges on our ability to recognise these changes, adapt and innovate. The sooner we understand and embrace this, the better equipped we will be to navigate the challenges ahead, turning the ‘end’ into just another beginning.