As I have often written (here or here for example), demography is a fascinating subject whose impact on economy is complex and wide-ranging. Indeed, demography, while often overlooked, plays a vital role in shaping our world and its future. Amid declining birth rates and an aging population worldwide, understanding the factors that influence fertility rates is paramount.

This week, after a couple of conversations in the office, I have decided to turn my gaze towards the situation of working parents in Switzerland, the country I have been lucky to live in for the last 6 years (and counting, hopefully). Switzerland, world-famous for its enchanting landscapes, high quality of life, and robust economy, is seemingly a children’s paradise. Its pristine natural beauty and a myriad of family-friendly activities make it an ideal playground for kids. However, data (and the reality) narrate a different story.

Looking at the facts

Fortunately, demography is an area which is fairly well and consistently analysed across a wide range of countries, facilitating comparisons.

First, it is interesting to note that, indeed, existing rankings of family-friendly countries consistently put Switzerland far from the top of the list – 30th in the OECD according to UNICEF, 22nd out of 30 countries according to travel agency Asher & Lyric, 13th in a USA Today survey etc.

This absence of perceived kid-friendliness is reflected in the low fertility rates – or, to put it more poetically, the number of kids women decide to have. According to the OECD, in 2021, the average Swiss woman had 1.46 child, which is slightly below the OECD average of 1.59 and much lower than the replacement rate of 2.1 required to maintain a population stable in the long run.

How can we explain these findings?

Deconstructing the Paradox: The Interplay of Economic and Societal Factors

To understand the ‘Swiss paradox’, we need to delve into some key economic and societal factors at play. One stark aspect of Swiss life is its high cost of living. The cost of everything from basic necessities to leisure activities is considerably high, making Switzerland one of the most expensive countries to live in worldwide.

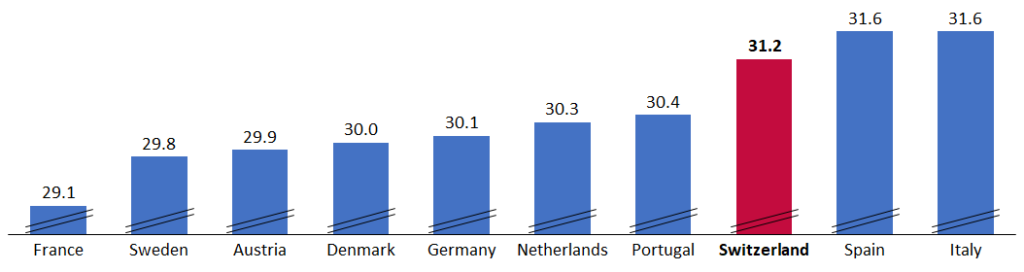

The high cost of living impacts family planning decisions. First-time mothers in Switzerland are among the oldest in all OECD countries, indicating a trend of delayed parenthood. This delay is often a result of couples waiting to achieve financial stability before starting a family.

Housing also represents a challenge in Switzerland. Not only is this a significant expense item (with an average house-price-to-income ratio of 128% according to Statista), but the very availability of housing is, in some regions, problematic. In September 2022, the vacancy rate across Switzerland was a mere 1.31%, and even lower than 0.5% in economically dynamic areas such as Zug and Geneva. This makes it hard for families to find appropriate, affordable accommodations and hampers their mobility.

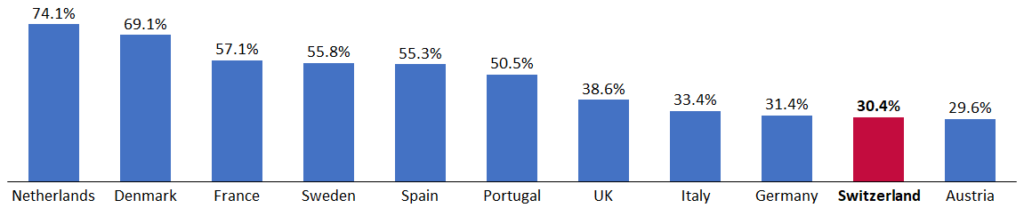

A closely related challenge is the high cost and limited availability of childcare infrastructure. It becomes a juggling act for parents to maintain their careers, even part-time, and take care of their children. Although part-time work is more prevalent in Switzerland than in many other countries (60% of women and 17% of men work part-time, according to the OFS, compared with respective averages of 26% and 6% for the EU-27), the scarcity and expense of childcare often deter parents from choosing to have more children.

Compounding these issues, compulsory schooling in Switzerland begins relatively late, at around age 5. Moreover, the school hours, especially in the early years, are quite short, placing an additional burden on working parents who must arrange for childcare outside of school hours. I was surprised to note how important the familial support system was in Swiss society. Parents tend to lean heavily on their own parents for childcare help. But the challenge remains for “immigrant” families who cannot count on close family support.

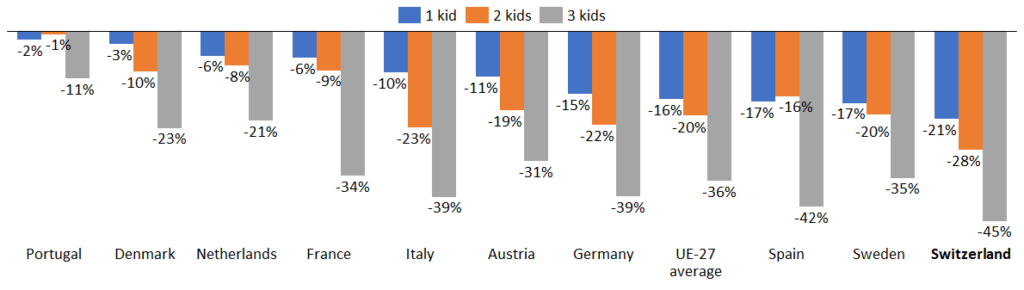

All in all, the financial burden for families in Switzerland is real. By the Swiss ONS’s own admission, raising 3 kids in Switzerland equals to reducing a family’s standard of living by 45%, compared with 11% in Portugal or 21% in the Netherlands.

A Call for Action

So, how do we get away from this perilous situation?

Currently, Switzerland, like many other (developed) economies, primarily relies on immigration as a band-aid to supplement its dwindling workforce. Immigration can however become a ‘zero-sum game’ if we enter a labour supply constraint situation at a global scale. I think it is high time to rethink this approach and develop long-term, sustainable demographic strategies.

Children are much more than the personal joy and sense of pride they bring to their parents. They are the building blocks of our future, the workforce of tomorrow. An economist would say that, by having and raising children, parents generate ‘positive externalities’ for the economy. Following this train of thought, economic theory argues that society as whole, through the State, should ‘subsidize’ parents using a range of monetary and non-monetary incentives to encourage this behaviour. Besides addressing the root causes previously mentioned (cost of life, affordability and availability of housing and children care infrastructure etc.), policy changes like enhancing access to parental leave coupled with tax incentives can be instrumental.

Scandinavian countries provide good case studies, offering a mix of high-quality, affordable childcare, and generous parental leave policies. Unsurprisingly, Sweden and Norway regularly rank at the top of the most family-friendly country lists, and their birth rates tend to be slightly higher than the European average. Another example is France, where family-friendly policies have contributed to maintaining one of the highest fertility rates in Europe – in this regard, I am always surprised by the (relative) ease with which my friends who have stayed in this country can find a nursery place for their children, and by the multitude of financial aids implemented by the French government.

To conclude, the issue of demography extends beyond a mere analysis of birth rates and population sizes. It is a prism reflecting a country’s socio-economic health and its future trajectory. In Switzerland’s case, it highlights a pressing need to create a more family-friendly environment that values and supports parents, encouraging them to have children.