The landscape of higher education, a field I have been personally involved in, is in a state of disarray. This week and next, I would like to focus my analysis on this crucial sector, echoing sentiments expressed this week by both the Financial Times and Le Monde. On both sides of the Channel (among other developed countries), the higher education system is caught in a vortex of (interconnected) crises, mixing a significant funding shortfall, a discrepancy between the supply and demand of skills, and an inability to effectively regulate private education. How have we reached a situation where universities are losing money with each additional student they accept? Why doesn’t a Master’s degree guarantee young graduates a job anymore? How is it that higher education programs can expand with seemingly no state control?

Challenge #1: Unravelling the Funding Crisis

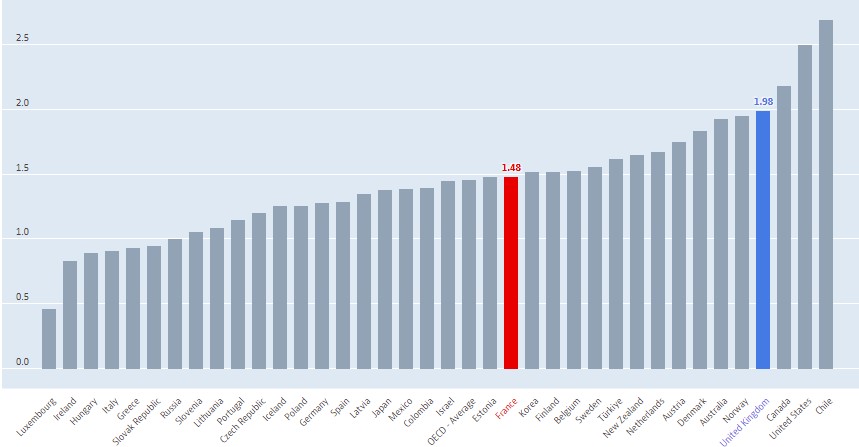

The first systemic failure hinges on the vast underfunding of the entire public system. Looking at the UK, the Financial Times article reports that UK ‘Russell Group‘ universities face a staggering funding shortfall of around £2,500 per domestic student, an amount even more surprising given that the UK devotes one of the highest shares of GDP to higher education (almost 2% in 2020) in the OECD.

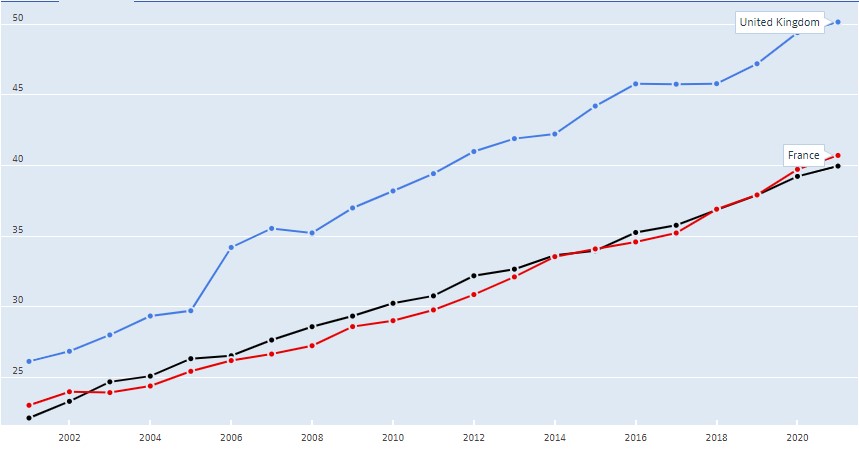

The introduction of a contribution system in the early 2000s, revised in 2012, was an attempt to close this funding gap. However, it has failed to do so. The revenues generated by domestic students alone, which is a maximum of £9’250 per head at present, simply falls short of covering operational costs. To mitigate this risk, UK universities have been increasingly relying on international students, who pay at least twice the tuition fee, to subsidize domestic students. And yet, international student numbers may dwindle due to geopolitical tensions, further straining financial resources and restricting the number of seats open to domestic students.

Moreover, what is needed today is not a reduction, but an increase in capacity. The Financial Times (again), using population forecasts from the Office for National Statistics, expects a shortage of 45,000 university places in the UK by 2030. This stark divergence between financial needs and available resources forms the first axis of the education system’s triple failure.

In France, the State currently subsidizes universities almost entirely. President Macron’s attempt to make students contribute more has been challenged by the Constitutional Council, which argued that access to free higher education should remain a right of each citizen. The under-funding of universities remains a problem that is regularly raised and, for the time being, largely unresolved.

It is important to note that the funding crisis is not isolated but intricately connected to the other issues plaguing the higher education system. The lack of adequate funding restricts universities’ abilities to adapt and innovate their curriculum to meet evolving skills demand, further exacerbating the skills gap. Additionally, underfunding of public institutions might indirectly fuel the unregulated growth of the private sector, where quality assurance becomes an even greater concern.

Challenge #2: Navigating the Skills Gap

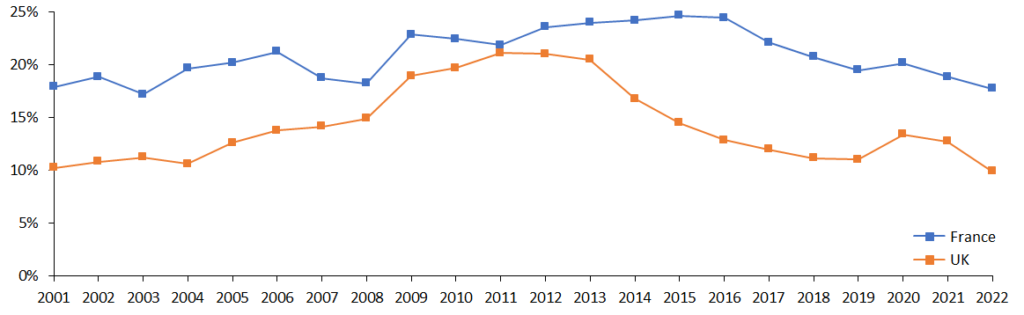

The second failure is the persistent misalignment between the skills our education systems supply and the demand from our economies. This discord has spurred a global sprint towards tertiary education, increasingly perceived as a ‘safe haven’, across almost all developed economies.

Unfortunately, if led blindly, without true government steer, this race generally results in a ‘zero-sum game’ with limited effect on youth unemployment, a phenomenon we have witnessed in both France and in the UK.

In a bid to remedy this, UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak has proposed to restrict enrolment in “low value” courses, using graduate employment and dropout rates as markers. However, this approach draws significant criticism. Detractors argue that it unfairly targets students from disadvantaged backgrounds and could prompt universities to inflate the length of studies or retain unsatisfied students. Instead of addressing the misalignment, it could ‘trap’ students in an academic path where they might better serve society and fulfil their ambitions elsewhere – an inefficient and thus societally costly outcome.

The skills gap is inherently tied to both the funding crisis and the regulatory issues within the private sector. Without sufficient funds, public universities struggle to update their programs to meet market demand for skills. Moreover, as students flock to private institutions that promise skill-based programs, regulatory lapses may allow subpar programs to flourish, leaving students with qualifications that may not meet market expectations.

[To be continued next week…]