Last week I finished my reading of Nouriel Roubini’s latest book, MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, And How to Survive Them – and yes, the content is as scary as the title may suggest. Over a little bit more than 300 pages, Mr. Roubini examines 10 risks that, in his view, will create major economic havoc in the next decades, from excessive debt to climate change and the rise of AI. I do not share Mr. Roubini’s heavy pessimism on all fronts (he is nicknamed ‘Dr. Doom’ for a reason after all) but his chapter on the consequences of the ageing of the population (simply called ‘The Demogaphic Time Bomb’) is worth a read.

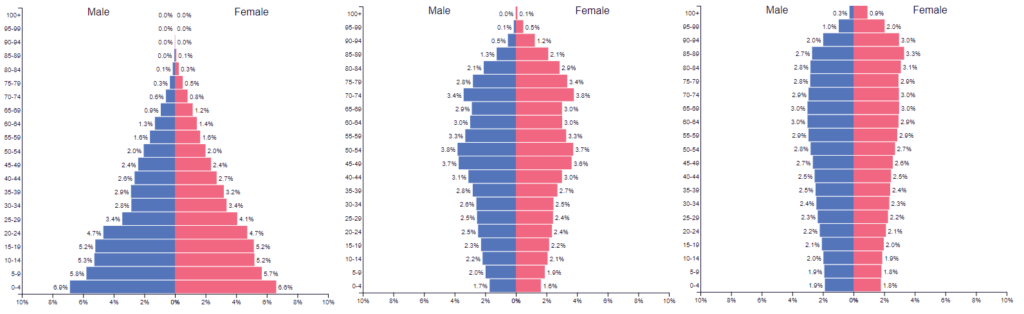

For almost a century, developed economies have been relying on social solidarity programs, by which professionally active individuals would financially contribute to the retirement of the elderly, with the view of becoming ‘financed’ a few decades later. This system worked well at its infancy, with a young and growing population. Now, says Roubini, with populations ageing, the burden on the working class is becoming increasingly unsustainable – too few working people for too many pensioners. Japan is probably a case in point in that respect; population peaked in the early 2010s to 128m, is now closer to 124m and should drop to c.75m in 2100, according to the website Population Pyramid. In his book, Mr. Roubini highlights the example of Poland, whose population will go from 38m in 1995 to 32m in 2050.

Source: populationpyramid.net

Solving the upcoming ‘pension conundrum’ has made its way to the top of policy-makers’ agendas, who often have to battle with ‘High Street’ to bring unpopular reforms into force – most recently in France, where more than 1m people took to the streets to defend ‘leurs acquis sociaux’. Postponing retirement, reducing benefits, increasing contributions, increasing public debt: the remedies are all known and it is now up to each government to decide on which ones to trigger, and how fast. The current system cannot hold, arithmetically, and with only the status quo all economies will hit a wall sooner or later. Here we must agree with Roubini.

I would nonetheless not consider the threat as a ‘ticking time bomb’, for two reasons.

First, the situation is not binary (‘safe or blown’), but more of a continuum, where public debt and, ultimately, increased taxes, reduced State spending and/or inflation will play the role of saviour of last resort. One can always fill a financing gap by printing more money – but then one needs to pay back (by levying new taxes or cutting spend) or the money loses in value (through inflation).

Second, a time bomb is harmless until it explodes. Here, the situation has already started to worsen, with pension scheme deficits starting to widen. In that respect, the time bomb is more akin to ‘Betonamit’, a liquid poured into concrete and which, once dry, gradually causes it to explode – don’t get me wrong, I’m a (very) poor handyman.

How much Betonamit is already into our system and how quickly we can stop pouring more will depend on the efforts we are ready to make from now, not just in the distant future.