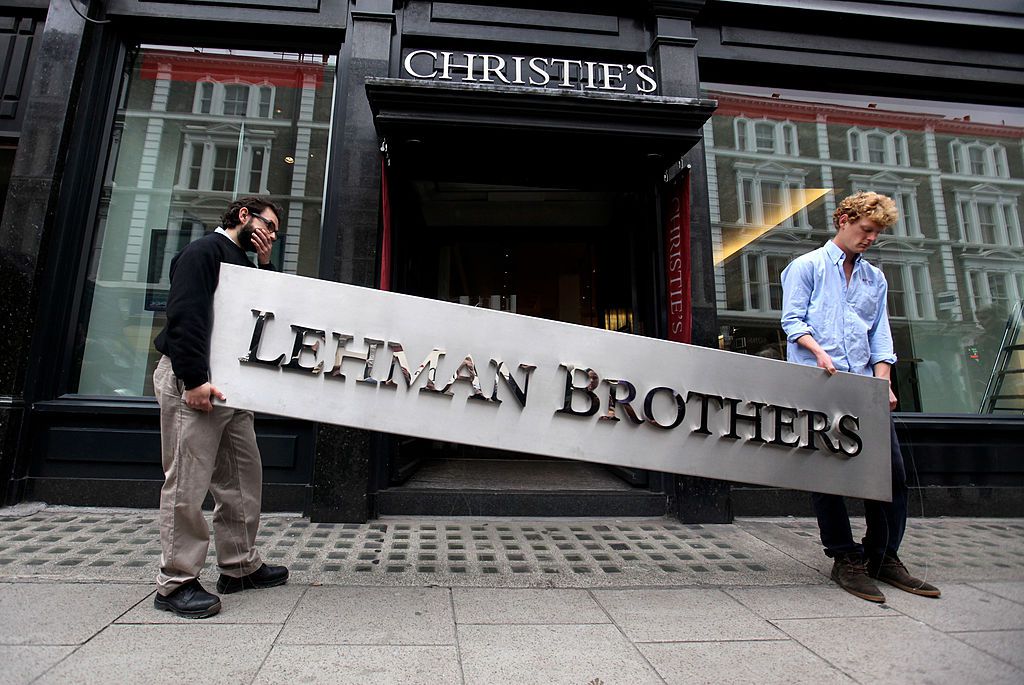

The economic news was dominated this week by the resounding bankruptcy of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a bank based, as its name may suggest, in California. More than the potential losses at stake (we are dealing with USD200bn of deposits, which the US government has ultimately decided to protect entirely), this failure symbolically reawakens the old demons of 2008, when Lehman Brothers, a bank of a completely different scale and history, had to close down. In both cases, excessive risk-taking and a sudden reversal of fortune were to blame. The parallel stops here, though.

Unlike the Lehman case, the SVB story represents a perfect example of ‘asset/liability mismatch’. In corporate theory, a company relies on ‘liabilities’ (typically debt and/or stock) to fund the purchase of ‘assets’ (factories, raw material etc.). A couple of definitions now:

- Each asset features a certain liquidity level which, according to Investopedia, “refers to the ease with which an asset, or security, can be converted into ready cash without affecting its market price” (the most liquid asset is… cash, obviously, the least being for instance a super-specific factory which you would not be able to get rid of without a significant discount).

- Each liability has a certain maturity which (thanks Investopedia again) is “the agreed-upon date on which the investment ends, often triggering the repayment of a loan or bond, the payment of a commodity or cash payment, or some other payment or settlement term.” When you borrow money over a 30-year period to fund the purchase of your house, the maturity is 30 years.

Optimizing the balance of assets and liabilities (known together as ‘the balance sheet’) is actually more difficult than it seems. A good CFO needs to ensure that you have sufficient funding but not too much, otherwise you will pay interests or dividends for funds you are ultimately not using. Similarly, having cash sitting at the bank helps to pay short-term bills (which typically have a very short maturity), but too much uninvested cash is wasted money – unless you are Scrooge. Good practice would nonetheless dictate that the value of your short-term assets (i.e. the assets you can liquidate with relative ease) should be at any time greater than the value of your short-term liabilities (i.e. the money you may be required repay soon).

Within the investment landscape, mutual funds invested in real estate are prime clients for maturity mismatches. Financial institutions marketing these funds offer clients the ability to withdraw their funds at any time, even though their deposits are currently invested in real estate, a typical illiquid asset that cannot be sold overnight without a steep discount – an outcome known as ‘fire sale’. Fire sales are not harmless, because they crystallize losses and can as a result significantly worsen the financial situation of some depositors, which in turn must make sales to keep their balance sheets afloat – the ‘contagion effect’ that governments and regulators try to avoid in any financial crisis. To mitigate the risk, these funds to renege on their promise by introducing a cap on redemptions when market conditions turn sour – Blackstone, among others, did so earlier this year.

Another well-publicized example of maturity mismatch is WeWork, which contracts long-term leases to then sublet in pieces for short periods of time, charging a mark-up for the flexibility offered in the process. Although the business model seems appealing in theory, it fails in practice, as soon as the vacancy rate starts to exceed a certain threshold. This mismatch represented a gaping hole in the company’s business model, which the COVID crisis only served to exploit.

Back to SVB. This bank was specialized in holding the money of start-ups in Silicon Valley and thus strongly benefited from the tech bubble which lifted its level of deposits (i.e. money raised by start-ups and subsequently deposited on their account) from USD61bn in 2019 to USD189bn at the end of 2021. For banks, deposits are ‘liabilities with 0 maturity’, i.e. customers lend the money and can claim it back whenever they want. With all this cash at hand, SVB decided to invest in a range of securities, including almost USD100bn in long-term US Treasury bonds, with a maturity greater than 10 years. In summary, SVB traded short-term liquid assets for long-term ones against the reward of interest rates, which at the time were near all-time lows.

The situation went awry earlier this year, when the tech sphere started facing difficult times. Some depositors needed some of their money back. Without enough cash at hand, SVB had to ‘fire sell’ some of the bonds at a discount (bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions and interest rates had gone up significantly since 2021), generating losses and, more importantly, significant public concern about the bank’s financial health. And yet, trust from its creditors is a bank’s most precious (intangible) asset. When depositors stop thinking that your money is safe in their bank, their first concern becomes withdrawing it while they can, effectively drying up all the bank’s liquidity in the process, known as a ‘bank run‘.

Some will see in this latest case the manifestation of a new ‘black swan‘, a term first used by Nassim Nicholas Taleb to designate unexpected adverse events of large magnitude. I would tend to disagree. SVB’s management made a terrible judgment call by investing way too much money in an illiquid asset, implicitly underpinned by the belief that the tech frenzy would go on for a decade or so, whereas economic history spanning over decades teaches us that booms and busts typically unfold over months or years. It is therefore difficult to assimilate the current context to the manifestation of an ‘extremely improbable event’.

Even if the US government decided to come to the rescue, the crisis may not be over yet and other banks may soon face similarly difficult (although largely unrelated) liquidity situations. At this point, a remake of 2008 cannot be excluded.