The idea of a 4-day workweek is certainly not a new one. The conversation around it started as far back as the 1950s, with academic papers on the topic dating back to the 70s, and yet, it remained a largely dormant concept with only 5% of employees globally subscribing to this schedule in 2020, as per a Gallup survey. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has reignited interest in this model and a growing number of countries and companies has been considering to implement this model. In a world where our approach to ‘human capital management’ neds to be thoroughly rethought, what shall we think of this shift?

Unpacking the Multiple Forms of a 4-Day Workweek

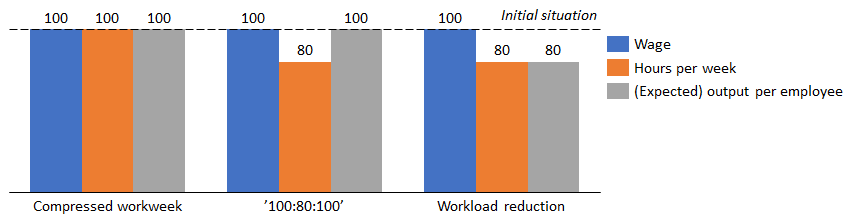

First, I would like to highlight that what we call ‘4-day workweek’ actually groups together 3 main policies with different practical implications:

- The compressed workweek: Here, the overall workload remains constant, but the working hours are compressed into fewer days, leading to longer workdays.

- The ‘100:80:100’ model: This model retains the original workload but trims the hours by 20% through a combination of productivity-enhancing tools, processes, and practices. ‘100:80:100’ stands for ‘100% wage, 80% hours, 100% productivity’ – cannot get much clearer.

- A proportional workload reduction: This version scales down both the workload and the working hours by 20%, leading to an equivalent 25% rise in people costs.

Understanding the Current Appeal: The ‘Why Now?’ Factor

A number of circumstances have combined to thrust the 4-day workweek into the limelight. In the present scenario, companies are battling the challenges of a highly competitive job market, endeavoring to attract and retain top talent. In such a scenario, a 4-day workweek is seen as a coveted non-monetary perk, not unlike the option of remote work. A Forsa survey revealed that a staggering 75% of participants in Germany find the 4-day workweek a desirable proposition.

The work-from-home routine ushered in by the pandemic served as a catalyst to show that an increase in productivity is achievable with the implementation of smarter work practices, like shorter and more streamlined meetings. At its core, a 4-day workweek indeed demands the dissolution of inefficient processes and stifling bureaucracy. It amplifies the perceived value of work, thus enhancing the overall sense of job satisfaction. Moreover, it offers employees the liberty to manage their week more efficiently.

Beyond the surface appeal, this shift could also materialize into indirect monetary benefits for employees, through e.g. a reduction in childcare and transportation costs, as well as non-monetary benefits primarily in the form of additional leisure time – although, as previously explained, not all ‘4-day weeks’ are created equal.

So far, these different models seem to yield generally positive outcomes for both businesses and employees. There is an upswing in wellbeing and a decline in burnout rates. An impressive 97% approval rate was reported after a December 2022 trial, signifying that companies and employees alike are eager to sustain this work arrangement.

Recognizing Potential Roadblocks and Concerns

Nonetheless, the transition to a 4-day workweek is not without more or less visible complications, for instance:

- Debate remains open on the effect of the shorter week on engagement. Neither the “positive” nor the “negative” camps have yet been able to put forward the results of a sufficiently robust study on this subject.

- Some employees have voiced increased stress levels due to the pressure to squeeze five days’ worth of work into four.

- This condensed schedule also risks blurring the distinction between personal and professional life, particularly if employees have to log on after work hours to complete tasks.

- From an economic viewpoint, the policy which consists in maintaining salaries while reducing the workload is equivalent to a 25% surge in people costs before any productivity improvement, which could exacerbate prevailing inflation problems.

- Also, akin to remote work, a shorter workweek could limit chances for informal interactions and spontaneous, serendipitous exchanges since not all employees would be in the office simultaneously. This objection is one of the main reasons why a growing number of companies are asking employees to give up their home workstations and return to the office.

- Finally, a more significant concern is that a 4-day workweek could inadvertently widen the societal gap between those who can and those who cannot compress their weeks—groups that often mirror those who could or couldn’t work remotely during the pandemic. We run the risk of creating a two-tier society, with the upper echelon gathering all monetary and non-monetary advantages. The cohesion of our Western societies is becoming an ever more pressing problem as inequality increases. The 4-day week will unfortunately do nothing to ease these tensions.

The rising momentum around the 4-day workweek seems to echo the trajectory of the remote work trend. Both belong to the family of tantalizing perks that companies might be willing to offer while the job market favors employees, but its permanence is uncertain. Reversing such a trend, however, may prove challenging due to its structural impacts on work organization.

In any case, viewing the 4-day workweek as a silver bullet for challenges like employee recruitment, retention, and engagement is a superficial approach. I believe the real solutions lie deeper, in fostering a comprehensive improvement in company culture and values – a much deeper driver in my view. The goal for businesses should be to create an environment where employees feel valued, engaged, and empowered, irrespective of the number of days they work each week. The 4-day workweek might be part of the solution, but leaders should not perceive it as an ‘easy and lazy’ substitute for deeper organizational challenges.