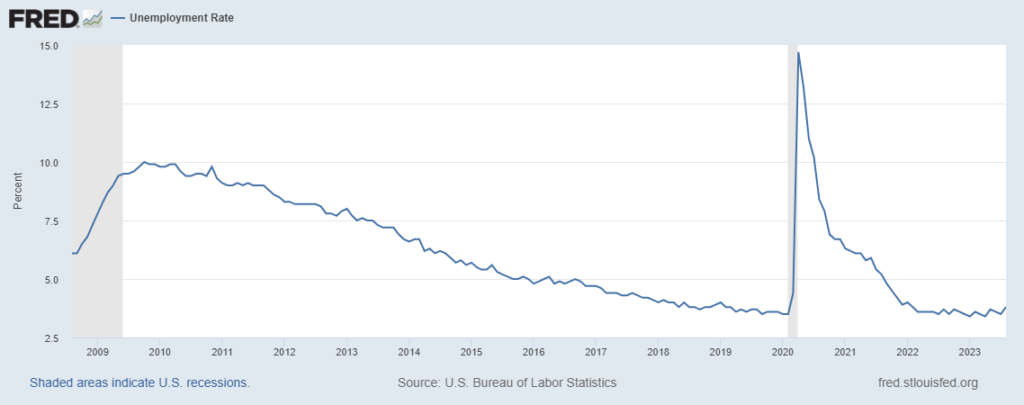

My eye was drawn this week to an (old) Forbes article describing the loss of momentum of “white-collar workers” in the job market, and the sense of panic that this instability could create in some people. The situation is paradoxical (the unemployment rate is still close to its lowest historical levels in most developed economies) and relatively unprecedented (in these same economies, blue-collar workers have often been the first targets of economic layoff plans).

The author of the article confirms the impression: yes, professionals in office activities (more picturesquely called “knowledge workers”) could be more likely to lose their jobs. The article cites three major factors to explain this phenomenon: (i) the use of outsourcing, (ii) the rise of artificial intelligence, and (iii) recruiters’ hesitancy in the face of deteriorating macroeconomic conditions. As much as I was in complete agreement with the observation back in February (and still am), I am (partially) in disagreement with the diagnosis.

The COVID crisis has, I believe, acted as a catalyst on two fronts. It first forced all company employees to move into a completely virtual and borderless world, beyond the sales forces or IT teams already accustomed to this mode of operation. The friction related to location has thus largely faded and has reduced the cost of outsourcing teams—in a fully virtual world, providing an office for each employee is no longer a prerequisite. However, after experiencing the “magic” of all-virtual, it seems to me that an increasing number of decision-makers are becoming aware of the limitations of this model and that we will gradually return to the traditional office model, possibly with some telework adjustments at the margin. As I expressed in my article from February, the speed of change will depend, among other things, on the evolution of the labor market and the balance of power in negotiations between potential employers and candidates, a balance still rather favorable to the latter. Telework is here to stay, I am convinced, but the threat of a massive outsourcing of skilled jobs to low-cost countries seems particularly pessimistic to me.

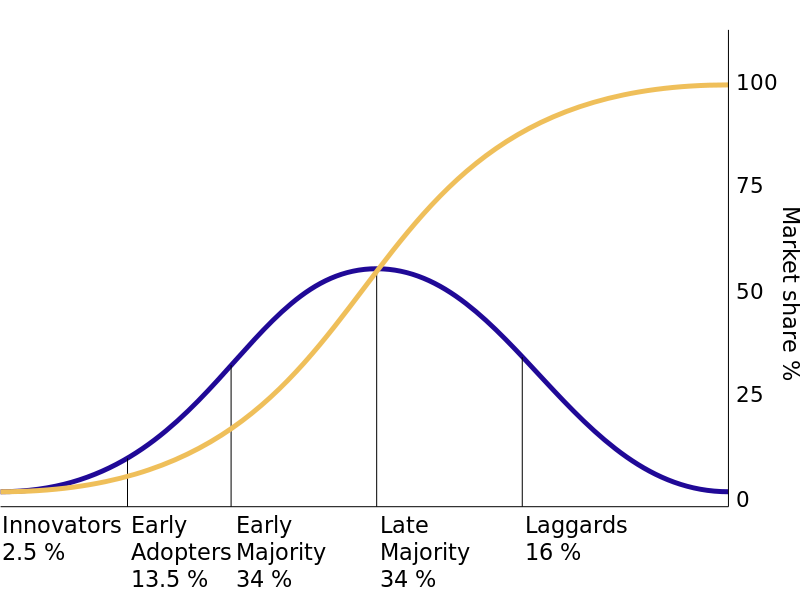

Similarly, I think we are overestimating today the impact and/or the speed of adoption of artificial intelligence in organizations. The stock market frenzy we are witnessing around this sector, starting with chip manufacturer Nvidia, seems fueled by demand coming from states and a few research-focused companies—the population that diffusion of innovation theory calls “innovators.” We still have a way to go before artificial intelligence truly reaches the core processes and ways of working in a company—and when it does, what will its real impact be? Sending a few sporadic queries to ChatGPT doesn’t seem to me to constitute, for the moment, a tectonic shift in the way of working.

On the other hand, the COVID crisis has subjected organizations to extreme stress and forced them to focus on their vital processes, thereby isolating non-essential activities and therefore employees whose added value is not essential to the company, regardless of their skills—in fact, a very competent employee can operate in a suboptimal role and not contribute value commensurate with his potential. For now, the consequences for employment seem limited to me for two reasons. The first is due to the dynamism of the post-COVID economic rebound, as it is difficult in some countries to part with a large number of employees if the employer’s economic health is good. The second is related to the tightness of the labor market and the “opportunity cost” associated with layoffs in a context of a shortage of job seekers: the company may prefer to keep an employee, even if he does not contribute to his full potential, in order to have the option to redeploy him later rather than immediately lay him off, save in the short term, but face the (more costly) obligation to recruit again in case of increased activity.

In any case, the context of near-full employment that we are experiencing in some sectors is unprecedented and is not set to last. Therefore, we should expect to feel, both blue-collar and white-collar workers, pressure on employment in the coming months. As I have already had the opportunity to write elsewhere, the return to macroeconomic normality will allow, after a possibly painful transition period, the economic fabric to regenerate and thus for employees to find a meaningful and valuable place in the economy and society.

“I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear.” — Nelson Mandela