In June of this year, the US Senate reached a last-minute agreement to raise the nation’s debt ceiling, previously capped at a staggering $31.4 trillion. This adjustment allows the government to borrow without constraint until January 2025. Meanwhile, in August, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported that the total credit card balance in the US surpassed the $1 trillion mark for the first time. Overseas, China’s largest property developer, Country Garden, defaulted on its international debt. Given the backdrop of escalating interest rates and a decelerating economy, the issue of debt has become pressing enough to warrant a dedicated discussion.

Modern-day debt enables a debtor to obtain additional financial capital, while simultaneously rewarding a creditor for providing that capital. This arrangement embodies an economic principle known as ‘intertemporal choice and budget constraint‘, where parties opt for more today at the expense of having less tomorrow, and vice versa.

Today, I’d like to delve into why debtors assume debt and the costs associated with it. Subsequently, I’ll touch upon prevalent trends and evaluate their potential ramifications.

Broadly speaking, entities – be they households, businesses, or governments – might seek to borrow capital for three primary reasons:

- To finance a productive venture, such as when a growing company constructs a new factory to augment its production capabilities.

- To cover immediate consumption or costs without generating long-term assets, akin to a household using a credit card to balance their monthly budget.

- To settle an existing overdue debt.

The first type can be termed ‘constructive debt’. If the venture is judiciously planned, the debtor can generate value surpassing the debt’s cost, resulting in mutual benefit.

While the second kind of debt isn’t ideal, it can be manageable if it’s a temporary solution to unforeseen circumstances, provided the debtor can repay it promptly. Examples might include unforeseen medical expenses or a brief period without income.

The third category, often dubbed ‘rollover’ debt, is typically problematic. This situation arises when a debtor cannot settle a debt within the agreed timeframe and requires additional credit, sometimes from the same lender, to clear the balance. Such a strategy is only viable until lenders become reluctant or demand exorbitant interest rates – which leads me to the next section.

Interest rates in credit arrangements signify the cost or benefit, contingent on one’s perspective – a ‘risk-reward’ assessment. To establish a rate, lenders consider:

- The rate they could attain by lending to a theoretically risk-free entity, often cited as the US Government, even though some level of risk is always present.

- The inherent risk in the transaction, or the ‘risk premium‘. This compensates for the potential of incomplete repayment. To assess this, lenders conduct thorough evaluations and also consult credit rating agencies like Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s – although they largely failed to anticipate the 2008 subprime crisis. When lending to individuals, their credit history becomes a significant factor. To mitigate risks, creditors might also secure assets that they can claim in the event of default, such as a house in the case of mortgage defaults.

If the reward (interest rate) is deemed inadequate for the perceived risk, lenders might be disinclined to engage unless the debtor offers a higher rate. Yet, severely financially troubled debtors might still fail to attract lenders regardless of the interest rate, often leading them towards bankruptcy – a looming concern for Country Garden.

The current financial landscape proves challenging for debt arrangements, for multiple reasons:

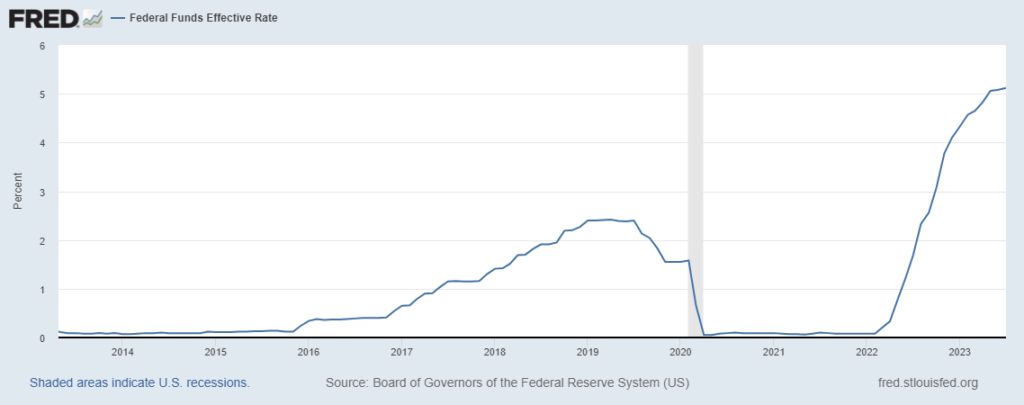

- Central Banks globally have been hiking their baseline interest rates to counteract inflation. Consequently, the rates for various credits have also surged.

- Concurrently, rampant inflation erodes household purchasing power. The repercussions are only partially alleviated by reducing certain expenses. This presents households with a twofold challenge: escalating credit card debts and higher interest rates.

- Post-COVID economic momentum has waned. For companies, this translates to diminished revenue; for governments, reduced tax collections.

- Thus far, the economic deceleration hasn’t adversely impacted employment. However, if job losses escalate, household incomes could be compromised.

- Compounding these factors, there’s the potential for a ‘credibility spiral‘. The current conditions erode the creditworthiness of households, businesses, and governments, prompting future lenders to demand heftier risk premiums. This can further deteriorate credit scores, potentially leading to inevitable bankruptcies in some instances.

While the outlook may appear bleak, solutions exist. A recurring theme in this blog is the advocacy for altered production and consumption patterns. At an individual level, it’s essential to prioritize essential expenses, reduce frivolous consumption, and save for future uncertainties. Financial literacy education can play a pivotal role in empowering individuals to make informed choices and stay out of debilitating debt.

For corporations, sustainable and responsible growth should be the goal. Instead of prioritizing short-term profits, companies must invest in long-term strategies that are not only profitable but also environmentally and socially responsible. By doing so, businesses can ensure they are equipped to weather economic downturns without resorting to excessive borrowing.

At the governmental level, policies must be in place to encourage sustainable practices both in production and consumption. This includes ensuring stringent regulations against predatory lending, and promoting transparency in financial transactions. Governments can also focus on bolstering the middle class, as a strong middle class can be the backbone of a resilient economy.

In essence, while the challenges of the current debt landscape are significant, they are not insurmountable. Through collective action, foresight, and a commitment to sustainable practices, we can navigate these economic hurdles and build a more resilient financial future.